by Pasquale Dattola

For twenty years, the EU-Mercosur deal has been stuck in a loop of negotiations and vetoes. While Brussels appears to be a victim of its own cumbersome process, Beijing has acquired the supply chain, and Washington has put up walls. The debate is no longer about trade; it is about survival in a rapidly changing world.

Overall, the agreement aims to establish a free trade agreement (FTA) between the EU Member States and Mercosur countries (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay), as well as to promote the diffusion of health and environmental standards among the countries joining. It would come after 20 years of negotiations among the multiple parties involved, and a complex ratification process that has turned the deal into a bureaucratic marathon.

Recent developments towards a final ratification have led to the resurfacing of political fragmentation. Two censure motions against the Commission failed. Yet the European Parliament remains divided, with the latest vote rejecting the deal by only 10 MEPs. Beyond Brussels, civil society engaged in several heated discussions, with farmers and environmentalist organisations opposing the agreement, claiming it would foster unfair competition from Mercosur countries and corrupt EU legislation on the Green Deal, even though the reality may be different, as this article will argue.

I. The Strategic Vacuum Europe Risks Creating

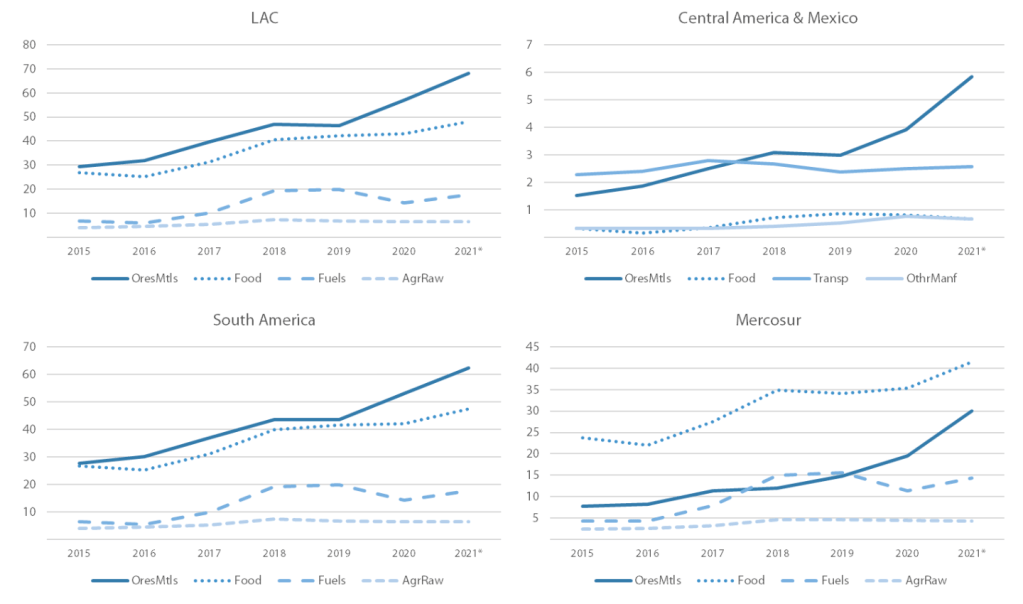

Europe’s internal paralysis has become China’s greatest diplomatic asset. China’s influence in the region is the most worrying factor for the Union, primarily due to Brazil’s role in creating the BRICS strategic cooperation and Beijing’s replacement of the EU as the leading trade partner of Mercosur countries. Most concerning for the Union’s productive sector is the loss of market leverage. In 2025, Chinese brands captured 80% of the Brazilian electric vehicle market. What Germany and France used to export, like machinery and cars, today is sold by China’s industry for 55% of the total value. Beijing has directly replaced Europe as the industrial engine of South America. All these data highlight not only the changing economic environment but also the risk of increased political cooperation that could weaken Western strategic links.

Sectoral exports to China by region, USD billion[TC3]

Source: European Parliament Research Service

II. The Supply Lines of the Future

This partnership goes far beyond agriculture; it secures the supply lines of the future, reducing problematic dependencies on unstable supply chains in Africa and Chinese processing hubs. This measure fits the broader diversification strategy outlined in the Critical Raw Material Act and will serve as a framework for increasing energy-sector production. The EU is a major producer of wind turbines and other renewable energy products, and Mercosur countries hold vast reserves of raw materials such as lithium and copper, which are essential to this growing marketplace. The deal is not only crucial for the reduction of export taxes, but also about creating a ’bi-regional value chain’, as Gonzalo Escribano, head of the Energy and Climate Programme at the Elcano Royal Institute, a major Spanish Think Tank, argues. As a result, the measure will be vital as an ‘anti-China’ insurance policy, limiting China’s influence in a strategic region.

III. Engaging the Critics: Farmers and Environmentalists

Opposition to the deal is strong and grounded in legitimate assumptions. The detractors are mainly farmers’ representatives and environmental activists, who claim that the agreement will harm farmers’ businesses and disregard ecological protection policies, thereby fostering deforestation and environmental damage. Critics argue it creates increasing social dumping, while not contributing to the diffusion of green practices in Latin American countries. While balancing social protection and environmental policies with the liberalisation of markets is the biggest challenge the deal faces, protectionist approaches are unlikely to deliver concrete solutions to the table, as long as China’s influence is becoming increasingly relevant in the region. As the recent Shein scandals in France demonstrated, weak regulation of trade exchanges won’t automatically protect either consumers or the environment, since globalisation eventually occurs with or without rules. Rejecting the deal means ultimately fostering trade without standards.

By contrast, the agreement provides the legal basis for enforcing the rules, as the EU has secured a legally binding commitment from the Mercosur countries to respect the Paris Agreement. Crucially, Mercosur countries must uphold environmental and labour standards or face suspension of trade preferences. To certify it, the agreement provides a monitoring system for environmental violations, therefore legally structuring the commitment. However, the question remains open as to whether the EU will be able to implement green practices effectively. Blocking the deal will not affect deforestation; it would simply mean the EU would have no tools to intervene, as current Chinese investment in the Amazonian forest is subject to no environmental conditionality whatsoever. Despite the legal implications of the deal, the real challenge is to put this on-paper effort into practice.

On the farmer’s note, while it is true that competition becomes fiercer, removing high tariffs with Mercosur allows for exploring markets in growth that were previously highly inaccessible to European producers. Currently, EU agri-food exports to Mercosur face tariffs from 10% to 35%. The deal slashes this to zero. We are not just opening a market, we are tearing down a wall that has made European goods uncompetitive for decades. By slashing trade tariffs, EU producers would gain a “first-mover advantage” over US/Australian competitors and avoid the spread of replicas of traditional EU foods at lower prices. The agreement, while simultaneously granting regulated access to EU markets for imports to boost competitiveness, also aimed to avoid saturating the market with Mercosur products. For sensitive products like beef, poultry, and sugar, the deal provides minimal import quotas, given the significant impact deregulation would have, therefore ensuring that 98% of the beef consumed in EU countries comes from the internal market. What’s also included are measures to support farmers severely affected by the agreement, such as a €6.3 billion fund to address market disruptions, and strengthened clauses in the event of import/export imbalances in these sectors, as shown by the Jacques Delors report on the subject. In the EU, the real challenge here is requalifying the productive industry, and liberalising markets is a decisive move Europe must take.

From a strategic perspective, the deal appears fundamental, beyond its economic benefits and environmental balance. The world is currently experiencing the controversies and backlash of Trump’s tariff war, which has shown once again that, in a vastly interconnected world, protectionist practices, while electorally appealing, are ultimately damaging. If the Union were to follow the same path, the repercussions would further weaken its already compromised role in the global landscape, as it would be unable to leverage its position through one of its strongest tools of negotiation: trade policy.

Image source: Generated by ChatGPT (header)