by Karen Natalia Yepes

In September, the 80th United Nations General Assembly edition took place with raising concerns regarding the state of the international status quo, a scenario in which multilateralism and democratic values are still the norm. Even though the summit’s topic was focused on keeping a commitment to multilateral organisations for safeguarding peace, interventions called for reforms and critiqued their legitimacy. Outspoken figures like Donald Trump did not hesitate to openly question the purpose of the UN, but at the same time, more modest figures like Alexander Stubb, president of Finland, also stated that the United Nations has been struggling to maintain peace and stability.

Indeed, the UN’s lack of agency represents a setback and perhaps justifies why powers are turning their back on the system. However, it is not the case for everyone. According to the European External Action Service, the EU and the EU Member states collectively make “the single largest financial contribution to the UN system, every year”, which represents one quarter of the UN regular budget and a third of agencies like UNICEF, WHO, UNDP, and UNRWA. Additionally, the EU figures as the world’s largest provider of Official Development Assistance. During times of uncertainty and recession, when most countries are returning to protectionist measures, the public might question the logic behind this funding.

European Union (2025). The starting point: a new landscape for Europe. In The future of European competitiveness. p. 18.

Some could argue that the EU has not accepted the international order shift and that it is falling behind in focusing on itself. Others could argue that they are allowing other states to keep their leadership and control via their veto power, despite them cutting their contributions. Nonetheless, besides safeguarding values and promoting solidarity, democracy and the rule of law, the reason is simple: it is a strategy.

Europe is not naïve. The bloc has acknowledged the changing power dynamics and has designed a roadmap to regain a relevant position as a world leader. This is contained in Mario Draghi’s report “The Future of European Competitiveness”, the white book of reform that inspired the ‘Competitiveness Compass’, which aims to tackle three necessities: closing the innovation gap, decarbonising the economy and reducing dependencies. Already by delving into Draghi’s report, one can understand the logic behind maintaining, at least temporarily, the mentioned contributions.

The EU has benefited significantly from world trade under multilateral rules.

Peacekeeping and geopolitical stability allowed the EU to overlook security investments and to import relatively cheap natural gas in times when it could rely on the US for defence and on Russia for energy. As a result of its openness, the EU was able to import the goods and services that it lacked and export the manufactured goods in which it specialised, which in numbers represented a rise in international trade as a share of GDP of about 13% during the first two decades of the 21st century. In contrast, the US only rose 1% in the same timeframe. [1] Nowadays, this context is fading away, as the relationships with partners have transformed and those dependencies in defence and energy have been turned into vulnerabilities. However, the EU can still – probably temporarily – rely on trade. Thus, investing in holding multilateral rules longer makes sense to maintain – even virtually – some stability.

Bonds with resource-rich countries still need to be tightened.

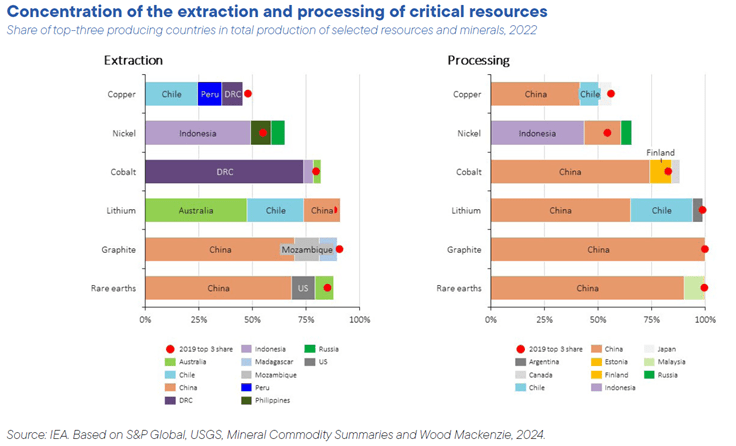

Major economies are racing against each other to secure critical raw materials (CRM) for key technologies, and Europe seems to be falling behind at every stage. Currently, the EU is dependent on non-EU countries for semiconductors, chips, hardware, and cloud services, and has little domestic capacity in multiple parts of the supply chain. It is true that China leads the production of certain commodities, but countries like Chile, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, Indonesia, and others can also provide those contested resources. Developing “resource diplomacy” that upgrades these countries from ‘developing countries’ to ‘resource-rich partners’ is a needed strategy to obtain supplies from ‘trusted’ providers. Therefore, the EU, being the major provider of aid, might be a good basis to build upon.[2]

European Union (2025). Increasing security and reducing dependencies. In The future of European competitiveness. p. 56.

In sum, the EU’s continuous investment in multilateral organisations and aid is not solely an altruistic act, but a strategy to hold the circumstances that have benefited it the most. However, it must not be taken for granted as a recurring payment. Europe knows that it cannot become a leader in new technologies, climate responsibility and remain as an independent player on the world stage at the same time. [3] In other words, keeping the contributions to the system is a way to endure the current challenges while it prepares for an up-scaled reform. That reform will most likely imply scaling back some of its ambitions, while addressing some institutional weaknesses that can transfer more agency to the bloc. All in all, the EU’s biggest asset is unity, and most likely its only way to try to catch up with the growing competitiveness. Thus, Member States should keep acting together.

[1] European Union (2025).The future of European competitiveness. p.13.

[2] European Union (2025).The future of European competitiveness. p.56-58.

[3] European Union (2025).The future of European competitiveness. p.7.

Header image source: https://unsplash.com/es/fotos/el-emblema-de-las-naciones-unidas-esta-en-exhibicion-frente-a-una-ventana-WVXJSJmA0Zc