by Roza Omarova

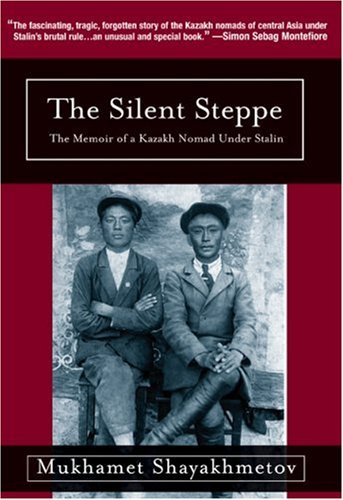

There is history known to everyone, history known by some, and then there is history that was almost lost. When your own history has been invisible to most, shedding light on it is the least you can do, hoping people will take interest and listen to you. In a world where some histories remain hidden, Mukhamet Shayakhmetov’s “The Silent Steppe: The Memoir of a Kazakh Nomad Under Stalin” emerges as a beacon of revelation. Shayakhmetov’s memoir offers a touching journey through the author’s life as a Kazakh nomad amidst the sweeping changes of Soviet rule.

Born in 1922 into a family of nomadic Kazakh herdsmen in eastern Kazakhstan, Shayakhmetov’s narrative captures an era marked by famine, political repression, and demographic shifts. This era’s legacy resonated throughout the 20th century, as evidenced by demographic shifts. After the famine of the 1920s and 30s, ethnic Kazakhs became the minority in their own motherland and it wasn’t until the 1990s that Kazakhs reclaimed their status as the largest ethnic group in Kazakhstan. These events echo the broader legacy of Soviet totalitarianism, with parallels to European history. Kazakhstan’s devastating famine during Stalin’s collectivisation policies exhibits similarities with the Holodomor in Ukraine – a trauma that is still shaping collective memory across post-Soviet states. Shayakhmetov’s story reflects not only on the resilience of the Kazakh people but also illuminates the enduring scars of Stalinist repression, relevant in European memory studies.

Breaking Nomadic Roots

Divided into three evocative sections – Class Enemy, Famine, and War – the memoir paints a vivid picture of life during a turbulent period in Soviet history. As Shayakhmetov recounts his childhood, he provides intimate glimpses into the nomadic lifestyle, from migration patterns to daily customs. Some of these traditions and ways of life were lost forever, while others can still be encountered in Kazakhstan today.

With his father arrested and their possessions seized, he and his mother face the harsh realities of survival in a changing landscape. Through Shayakhmetov’s lens, readers witness the devastating impact of collectivisation and famine, which claimed the lives of over a million people in Kazakhstan alone. Collectivisation was a set of Soviet policies aimed at disbanding individual farms and turning them into collective farms owned by the State. The regime under Stalin declared a fight against the class of presumably well-off farmers labelled kulaks. This meant that owning a horse, for example, could be regarded as a crime. Ultimately, these policies led to a catastrophic decline in agricultural production.

Even with the declared objectives of collectivisation, its effects resembled more those of genocide, especially in combination with the political purges that followed in the 1930s. The consequences of these tragedies are still felt today in Kazakhstan, where hardly any family is untouched by the loss of ancestors as a result of collectivisation or purges. Many families were destroyed, leaving no surviving members to honour them, and those who resisted the collectivisation were either sent to labour camps or executed. As a consequence, Kazakhstan’s population declined by over two million. The remembrance of this famine highlights the enormous influence of these occurrences since the country of Kazakhstan suffered for many generations before regaining the population it had in the late 1920s, before collectivisation began.

Shayakhmetov’s memoir stands out not for its sweeping theories or grand analyses, but for its focus on the raw, personal details of survival. The strength of The Silent Steppe lies in its portrayal of daily life under Soviet rule, where the Kazakh people, despite being forced into collectivisation, held onto their core values – hospitality, resilience, and community. The straightforward style of the memoir, though dry at times, reflects the starkness of the experience. His story, free from bitterness, captures the quiet endurance of a people shaped by tragedy, yet unbroken.

Recovering from the Past

This history not only resonates in Kazakhstan but finds parallels across Europe. As Kazakhstan regained its ethnic identity after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Eastern European countries worked in a similar manner to reclaim their national identities after decades of occupation and repression. Both Kazakhstan and countries like Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic states experienced the devastating impact of Soviet policies that uprooted rural communities, dismantled traditions, and forcibly reshaped demographics. These shared traumas continue to influence the countries’ collective memories.

Kazakhstan’s modern relationship with the European Union reflects the historical struggle outlined above. Like Eastern Europe, Kazakhstan has sought to align itself with Europe through strategic partnerships, engaging in trade agreements, education reform, and initiatives to strengthen civil society. Both regions aim to address human rights and foster democratic values while grappling with the legacies of Soviet oppression. For Kazakhstan, building ties with Europe offers a pathway towards political and economic security, mirroring Eastern Europe’s pursuit of stability through EU and NATO integration.

The preservation of memory is vital in both regions. Kazakhstan and many European countries have embraced projects that foster historical reflection and reconciliation, using their past to guide future development. Just as memorials and museums in Europe honour victims of totalitarianism, Kazakhstan too honours its own losses, ensuring that stories like Shayakhmetov’s are not forgotten. His memoir, The Silent Steppe, serves as a powerful reminder of resilience and the enduring scars of repression. It invites readers not only to reflect on Soviet history but also to acknowledge the resilience of nations that rebuilt themselves, both in Central Asia and across Europe. Through storytelling, both regions continue to remember, reconcile, and heal from their shared Soviet past.